Kalle reflects on Spatial Planning, the game changer most leaders overlook

Kalle reflects on Spatial Planning, the game changer most leaders overlook

Takeaway for leaders at all levels everywhere

Spatial planning is a dangerously underestimated aspect of sustainability

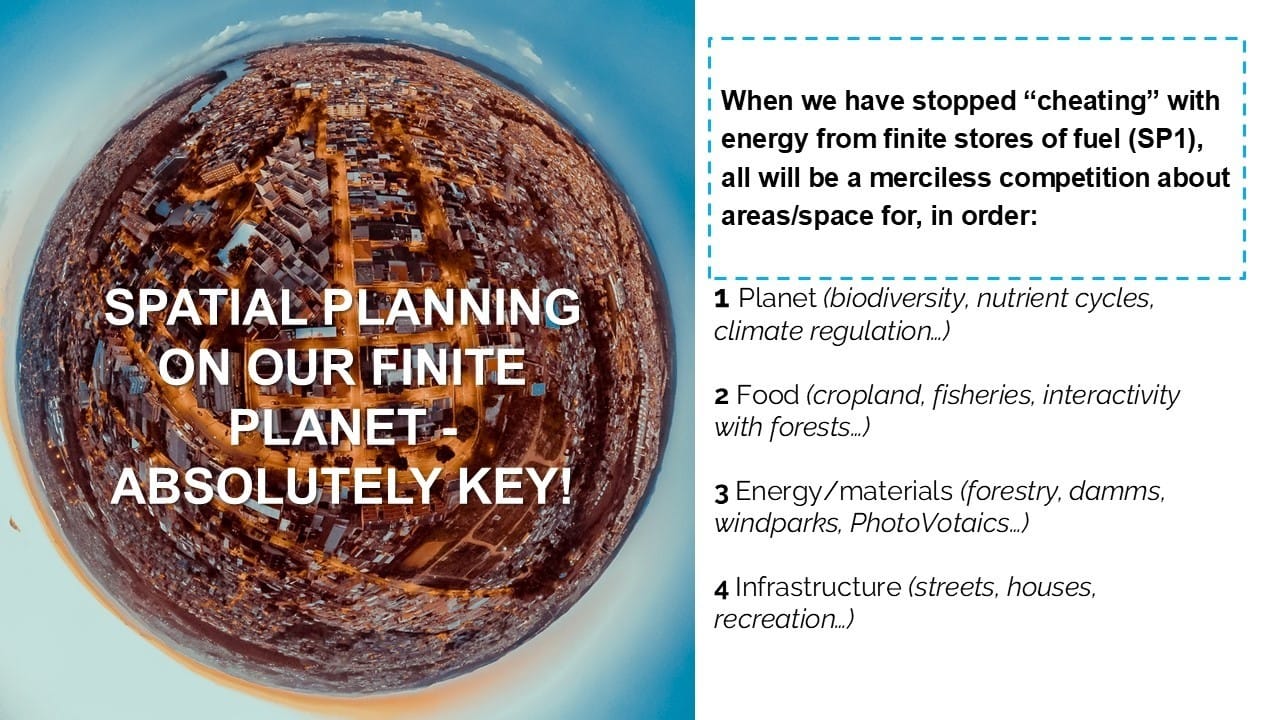

Our path to a sustainable civilization sits within clear boundary conditions, as articulated by the FSSD. Many debates already orbit this space: electrifying transport, phasing out fossil fuels, and realize nuclear power has no future. Yet one decisive dimension remains largely overlooked—spatial planning. When energy systems built on fuels fade and society must live within the “eternal” flows of sun, wind, hydro, geothermal heat, sea waves and ocean currents, what ultimately constrains us is not ingenuity alone, but land and sea area. These eternal flows may be free; the space to capture them is not. That is why spatial planning is a dangerously underestimated aspect of sustainability—and why every leader from city planners to CEOs must bring it to the center of strategy.

More in detail

Why linear fuels fail—and why that matters for land use.

Fossil and nuclear energy systems depend on linear flows of fuels that are depleted and paid for as they are used. Their costs rise both upstream (harder extraction, scarcer deposits, shakier supply,) and downstream (waste, cleanup, pollution, damage from climate change and accidents, social conflict). Thermodynamics and matter conservation are not opinions; they are facts. Either we let the linear systems phase themselves out through escalating crises and prizes in myriad dimensions, or we design the transition ourselves—intentionally, equitably, and early enough to avoid colliding with the funnel wall of diminishing capacity to sustain civilization. The global funnel of declining resource-potential from flawed societal design does not care about ideology.

Even before linear fuel systems fully unravel, the shift to renewables intensifies a fundamental competition for surface area. Unlike fuels, which concentrate energy in small volumes, renewable sources generally require more space to harvest comparable energy. The global flows of sun, wind, waves, currents, hydro, and geothermal energy dwarf our needs, but we can only capture them where surfaces exist, where nature can afford it, and where communities can accept it. In other words, sustainability becomes a spatial equation.

Spatial planning under FSSD: getting the priorities right

Within the FSSD’s ABCD framework, long-term success within robust boundary conditions for scalable solutions (“A”) must be translated into current challenges (“B”), a list of possible measures to deal with those (“C”) and prioritization of the concrete possibilitites into stepwise transitions (“D”). That translation hinges on spatial planning. A pragmatic priority order helps align decisions:

– First: Nature with its bio-geochemical cycles depends on biodiversity, functional habitats, and connected landscapes. They are profoundly area-intensive. Fail here, and nothing else is sustainable.

– Second: Food. Feeding a population that could still grow by billions requires fertile soils, water stewardship, and resilient agroecosystems. This, too, is very area-intensive.

– Third: Energy to sustain civilization. Energy flows beyond what nature and food systems need must be captured for civilisation itself . Such systems must grow, but not by undercutting the first two priorities.

– Fourth: Material production. Timber, fibers, medicines, and other bio-based materials have a role—but only within nature-positive limits.

– Fifth: Infrastructure. So, how much areas remain for housing, industry, mobility, and logistics and how do we plan for infrastructures such that they are compact, efficient, and synergistic with the higher priorities.

This order is not ideology; it follows from physics, ecology, and social stability. Degrade the first two, and food insecurity, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem collapse will cascade into human crises.

Spatial planning and the biofuel reality check

These priorities expose a hard truth: there is essentially no spare room for large-scale biofuels, except as narrow, transitional measures. The world has already hit the ceiling on land conversion for nature and food. Expanding biofuels at scale competes directly with nature, forests and farms, and risks worsening both climate and biodiversity outcomes. For communities already enduring hunger and displacement and eco-fugitives, this is not a theory—it is lived reality. The prudent path is to reserve biomass primarily for soil-improvements and materials with long life times, and short term targeted energy uses where no better alternative exists yet, while accelerating electrification and area-efficient renewable generation.

How to operationalize the transition: integrate disciplines early into joint ABCD workshoping

To make sustainable futures credible under “A” and actionable under “D,” leaders must knit together four domains:

– Resource knowledge. Understand the scale, quality, and renewability of resources—energy, materials, water, soils—and what is physically and economically scalable. This includes realistic assessments of mineral reserves and recycling potential for the energy transition.

– Spatial planning. Coordinate land, sea, and urban space to reflect the priority order above. This means mapping trade-offs, co-location opportunities, and cumulative impacts—not site by site, but system by system.

– Engineering and business model innovation. Design solutions that reduce area intensity, increase efficiency, and enable circularity. Think multi-use infrastructure e.g., wind over cropland, electrified rail, flights and shipping, and deep retrofits for saving/storage of energy on smart grids.

– Policy, economics, and governance. Mobilize capital and public consent through democratic processes: zoning reform, incentives for compact, mixed-use development, pricing that reflects externalities, and standards that drive efficiency and material recirculation.

The literature on strategic community and transport planning within the FSSD showcases how this integration works in practice and why it reliably outperforms ad hoc approaches.

Spatial planning examples that are already working

Forward-leaning, FSSD-informed leaders are translating these principles into tangible moves that can all be put on a C-list of options in organizational ABCD workshops:

– Phasing out biofuels except for narrow, time-bound use cases where no better alternative exists, while preparing for better use as soil improvements or feed stock to material production.

– Scaling regenerative, integrated agriculture and forestry that restore soils, boost biodiversity, and increase yields per unit area without chemical overload.

– Prioritizing area-efficient transport modes: electrified rail and waterborne freight, walkable and bikeable urban networks, and demand reduction through digitalization and better logistics.

– Co-locating land uses: wind turbines over cropland or grazing land; agrivoltaics where solar arrays and crops coexist; solar canopies over parking and canals; rooftop PV and facades that harvest energy without consuming new ground.

– Ending urban sprawl by committing to decentralized concentration: compact, polycentric cities with transit-oriented development, mixed uses, and green-blue infrastructure that enhances resilience.

– Planning infrastructure with nature: floodplains that double as parks, coastal buffers, and urban forests that manage heat while improving livability.

These are not marginal tweaks; they are structural reallocations of space aligned with the five priorities—and they deliver better returns on investment when measured across ecological, social, and financial dimensions.

Spatial planning is a leadership discipline

The FSSD provides the platform to ensure spatial planning is not forgotten in the rush to “green” technologies. Leaders who internalize the funnel logic, work backward from attractive futures modelled within robust boundary conditions for sustaianability. They prioritize space accordingly, to avoid dead-ends like overbuilding biofuel capacity or scattering renewables in ecologically critical zones. They will also find compounding advantages: lower energy demand through design, higher acceptance through fair siting, and faster scaling through integrated uses of land and infrastructure.

Sustainability will be decided as much by where we place things as by what we build. Spatial planning is a dangerously underestimated aspect of sustainability, and it belongs at the center of every strategy, from corporate portfolios to national policy and city plans. Put simply: if we get spatial planning right, we give ourselves the room—literally and figuratively—to thrive within the limits that make life possible. If we neglect it, even clean technologies will contribute to un-sustainability.

All hot topic Reflections are direct consequences of our Operative System.

For a deeper dive into the science behind the Operative System that informs all Reflections, see the peer-reviewed Open-Source paper with all its references: doi.org/10.1002/sd.3357. For the full title, see footnote below.

Or, for concluding reflections, practical insights and training, click on “Kalle Reflects” to see all reflections.

If you need any further advice, perhaps getting some further references, please send a question to us from the homepage.

Footnote: Broman, G. I., & Robèrt, K.-H. (2025). Operative System for Strategic Sustainable Development―Coordinating Analysis, Planning, Action, and Use of Supports Such as the Sustainable Development Goals, Planetary Boundaries, Circular Economy, and ScienceBased Targets. Sustainable Development, 1C16.