Animal Ethics and FSSD: Stunning Best Insights

Kalle reflects on ethics and animals

Takeaway for leaders at all levels everywhere

How does the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development (FSSD) relate to animal ethics? This question often surfaces in ABCD-in-Funnel workshops, and it’s worth pausing to consider a clear response. The short answer is that the FSSD—together with its operating system, the ABCD-in-Funnel—does not prescribe a universal moral code for how to live. Values, belief systems, and personal philosophies belong within the content of our visions and goals, which we develop inside the FSSD’s generic boundary conditions of any personal or organizational goal in the future . Still, it is valuable to explore how those boundary conditions can anchor conversations also around animal ethics, ensuring we don’t lose sight of fundamentals when the topic emerges.

The ABCD-in-Funnel gives us a structured way to ask the right questions about any redesign challenge—whether individually or for organizations, regions, products, or entire sectors. It helps us evaluate whether our plans are compatible with a sustainable future, in the literal sense of being possible to continue over time. The eight boundary conditions are designed to guide (re)design without replacing the ethical wisdom found in moral philosophy or religious traditions from the Golden Rule, to contemporary animal ethics by thinkers like Singer. Those philosophies provide the values-informed content of goals as well as values-informed pathways to get there; the FSSD provides the structure. With that in mind, let’s consider how the boundary conditions help frame animal ethics within sustainability planning.

The eight boundary conditions at a glance

In ABCD-in-Funnel planning, boundary conditions are divided into ecological and social dimensions. Together, they outline the basic constraints within which any possible civilisation in the future must operate.

– Ecological boundary conditions (three): In a sustainable future, organizations do not contribute to (i) systematically increasing concentrations in nature of substances from the Earth’s crust, (ii) substances produced by society, or (iii) degradation of nature by physical means.

– Social boundary conditions (five): Organizations and communities do not contribute to eroding social trust by structural obstacles to people’s (iv) health, (v) influence, (vi) competence, (vii) impartiality, and (viii) meaning-making.

Ecological boundary conditions and animal wellbeing

Consider the “A” in ABCD—the desired future. In a sustainable future, species extinction has ceased because our designs no longer violate ecological boundary conditions. While these conditions are often framed in bio-geophysical terms, they carry obvious ethical implications. A future that protects biodiversity and ecosystems is not only essential for human survival; it also aligns with ethical concern for nature at large, including animals and biodiversity in general. If we accept that healthy ecosystems are a minimum requirement for sustainability, then safeguarding habitats, preventing increasing pollution, and avoiding resource extraction that increasingly degrades ecosystems become non-negotiable. These actions reduce suffering and risk for animals simply by preserving the systems they depend on.

Social boundary conditions:

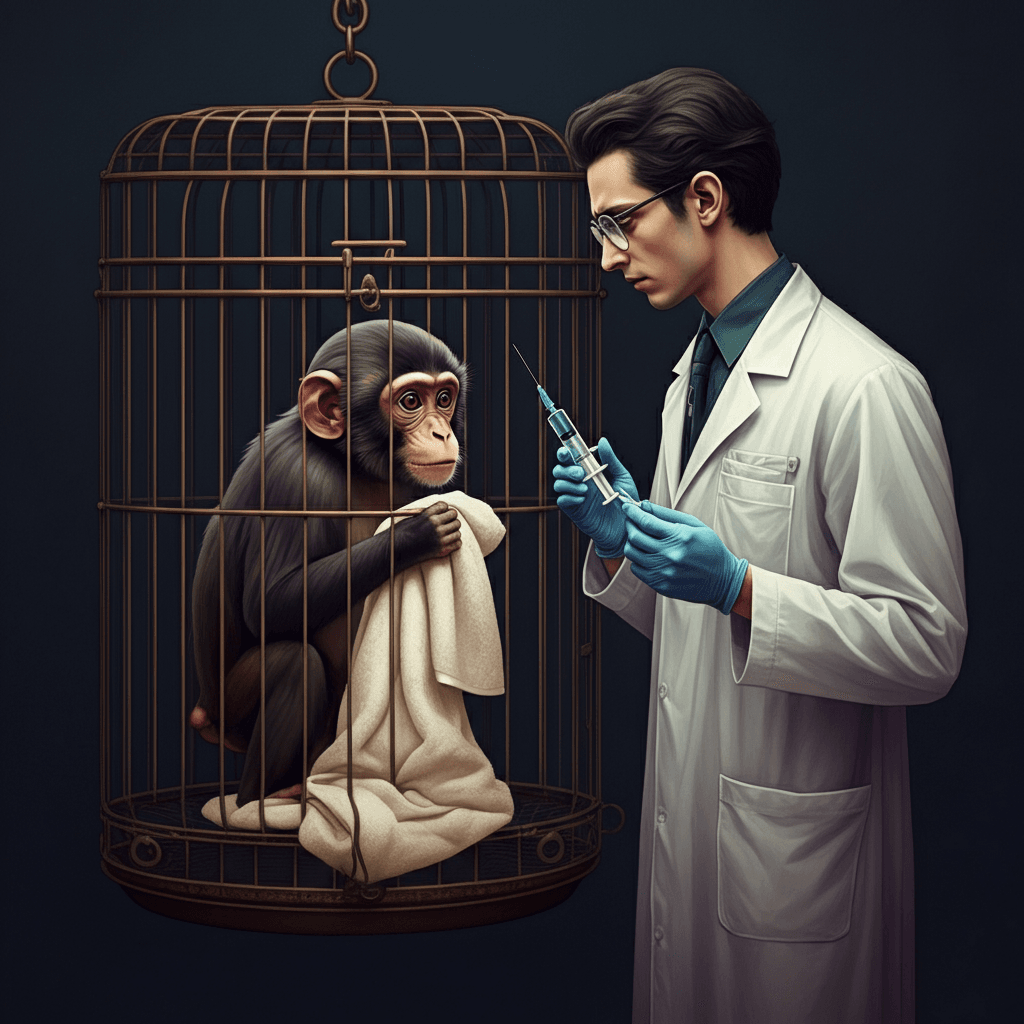

The social boundary conditions guide how we manage processes on the way to that future. They ask leaders and participants to co-create visions and pathways without putting structural obstacles in the way of health, influence, competence, impartiality, and meaning-making. This raises a challenging question for animal ethics: Could a social system, fully aligned with these five conditions, still be cruel to animals? For instance, might it permit painful animal experiments if they do not directly violate ecological boundaries?

Exploring that question in workshops can deepen ethical awareness. While we cannot directly include animals’ perspectives, the social conditions invite us to reflect on how our own health and moral wellbeing are tied to how we treat non-human life. They encourage us to:

– Consider whether our mental and moral health is compromised when our work ignores animal suffering (health).

– Allow the concerns of animals to be represented through human advocacy in decision-making (influence).

– Integrate learning and development that strengthens ethical sensitivity and practical competence in animal-related decisions (competence).

– Apply impartiality to interests beyond our own species, recognizing bias and power imbalances (impartiality).

– Build meaningful narratives and missions that connect our work to care for sentient beings and future life (meaning-making).

Applying the lens in practice: the cosmetics example

Take the cosmetics industry. An ABCD-in-Funnel process would define principles-aligned success (A), examine current practices (B) in that context, brainstorm creative solutions to bridge the gap (C), and prioritize steps (D) from C. Embedded in that process, animal ethics becomes art of a lens rather than an add-on. Teams might reflect on how animal testing affects employees’ sense of integrity and purpose, how to incorporate animal welfare considerations into R&D and procurement, how to upgrade competence around validated alternative testing methods, how to correct structural biases that default to animal testing when humane alternatives exist, and how to communicate a meaningful mission that includes responsibility for sentient life.

By grounding these reflections in the social boundary conditions, organizations can surface practical commitments: investing in cruelty-free innovation, redesigning supply chains, collaborating with regulators on alternative safety standards, and creating transparent reporting on animal welfare. None of this replaces philosophical debate, but it makes ethics actionable within the constraints of a sustainability strategy.

Learning, ethics, and advocacy across generations

Research in social dilemmas—such as Prisoner’s Dilemma experiments—shows that education and framing can significantly improve cooperative, ethical outcomes. This insight matters for animal ethics. Humans must act as informed advocates for those without a voice, whether animals, future generations, toddlers, or people unable to participate in decision-making. From an FSSD perspective, it becomes natural to integrate education that builds ethical competence and empathy into the planning process. Doing so strengthens social trust and expands the moral circle in ways that support long-term sustainability.

The social boundary condition of impartiality is especially relevant here. It reminds us to check for structural biases that silence or marginalize stakeholders—including non-human ones. Similarly, meaning-making asks us to articulate missions that carry moral weight. When organizations frame themselves as stewards for the voiceless, they create a narrative that supports consistent, principled action. This is not only ethically coherent; it can improve engagement, innovation, and public trust.

Conclusion: Keeping animal ethics in view within the FSSD

The FSSD and its ABCD-in-Funnel operating system do not dictate a moral doctrine. They offer a robust structure for sustainable (re)design and invite us to populate that structure with thoughtful, values-driven content. Animal ethics fits naturally into this approach. Ecological boundary conditions protect the systems that animals need to thrive. Social boundary conditions challenge us to consider health, influence, competence, impartiality, and meaning-making in ways that elevate concern for sentient life. When we use these conditions to guide our visions and actions, we keep animal ethics present in both our destination and our path—ensuring that sustainability is not just technically viable, but morally attentive to those who cannot speak for themselves.

All hot topic Reflections are direct consequences of our Operative System.

For a deeper dive into the science behind the Operative System that informs all Reflections, see the peer-reviewed Open-Source paper with all its references: doi.org/10.1002/sd.3357. For the full title, see footnote below.

Or, for concluding reflections, practical insights and training, click on “Kalle Reflects” to see all reflections.

If you need any further advice, perhaps getting some further references, please send a question to us from the homepage.

Footnote: Broman, G. I., & Robèrt, K.-H. (2025). Operative System for Strategic Sustainable Development―Coordinating Analysis, Planning, Action, and Use of Supports Such as the Sustainable Development Goals, Planetary Boundaries, Circular Economy, and ScienceBased Targets. Sustainable Development, 1C16.